The Viennese coffee house was invented by a spy. But the writers were the ones who made it legendary.

It was a secret agent who opened the first Viennese coffee house in 1683. His name was Johannes Diodato. He had bronze-colored skin, spoke Turkish and Arabic as well as the local dialects of the Ottoman Empire and owed his Christian first name to his Armenian background.

It was a secret agent who opened the first Viennese coffee house in 1683. His name was Johannes Diodato. He had bronze-colored skin, spoke Turkish and Arabic as well as the local dialects of the Ottoman Empire and owed his Christian first name to his Armenian background.

Diodato was the first cafetier in Vienna. Not Georg Franz Kolschitzky, to whom the first Viennese coffee house is attributed to. However, Kolschitzky – and this is certain – was the first who was given a license to serve coffee. Diodato’s inn is remembered as a “speakeasy” – as one call it today –, a secret meeting place that only few knew the address of and which had no sign at its door. One had to knock and say the secret password before you could enter.

It can be assumed that Diodato’s coffee house didn’t revolve around the coffee, but rather the people who drank coffee there and the messages they passed on. Due to his heritage, Diodato the Armenian was an expert at processing the rare raw material, which the Turks had to leave behind when they retreated from Vienna. With his coffee house he killed two birds with one stone: coffee and conspiracy. After a few years, however, his restaurant was suddenly shut down – for unknown reasons.

Georg Franz Kolschitzky, as can be read in historical reports, took years to come up with the right method of making coffee. In fact he managed to do so only just before his death. That did not matter to the Viennese, because they had no comparison; they drank coffee because it was new and enriched their cultural lives during culturally monotonous times. In addition, it was hot (rare for the beverage culture at the time), woke you up, and the coffee house offered a welcome change to the pubs drowned in wine and beer and where violent outbreaks were commonplace.

The coffee house, on the other hand, was a haven of tranquility, the first gastronomic establishment in Vienna, built around a cult beverage that determined a certain devotion when consumed. Enrichment instead of intoxication: this was the orientation given to the first cafetiers, respected people, most of whom came from the small group of the people at the Emperor’s court. As a result, the court, too, decided to taste the Turkish drink. And so coffee became acceptable for the upper class to drink.

Vienna, it is often said, was the first city to open a café. This is wrong, however, because the Ottomans had exported the bean to London before the second Turkish siege and taught the British about another hot drink besides tea. One that woke you up quickly.

Coffee could therefore be drunk all day long, especially if one had to stay awake: on the London Stock Exchange and the surrounding trading houses, for example. Coffee was as popular then as cocaine is on Wall Street today.

Coffee could therefore be drunk all day long, especially if one had to stay awake: on the London Stock Exchange and the surrounding trading houses, for example. Coffee was as popular then as cocaine is on Wall Street today.

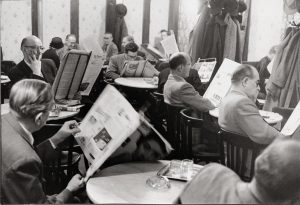

While the British refused to associate coffee with any kind of coziness (this was reserved for tea), the Viennese made it the center of their lifestyle – a combination of quiet relaxation and lively chatter. If a coffee house patron got tired, he sipped the next cup and was alert again. This could go on for hours, and as early as the time of Empress Maria Theresia, cafetiers were complaining about guests who sat around all day playing cards, betting on billiard, but not willing to spend any money. It was said at the time that these people probably didn’t have an apartment. Or too little money to heat their home. This may have been the case with some of these patrons, but going to the café wasn’t cheap – on the contrary, coffee was expensive as it came from Trieste or London, transport was costly and so you could hardly refer to it as the people’s drink.

The breakthrough for coffee and coffee houses did not come until a hundred and fifty years after Diodato and Kolschitzky opened their establishments for the first time. In the middle of the nineteenth century, coffee trade was so stable that there were hardly any shortages. Mocha replaced the infusion and a wide range of serving methods developed at various cafés, giving the bean’s cult a real boost. The Viennese papers, read mainly by a confident bourgeoisie, who fostered their Biedermeier lifestyle, sent coffee house testers all around Vienna, who were revered not for their regular praise, but rather their harsh critiques. The skilled Viennese knows what I mean.

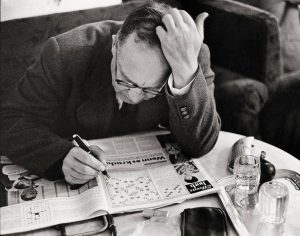

At the end of the nineteenth century the Viennese coffee house became the focal point of upscale Viennese gastronomy and many cafés turned into café-restaurants, large premises with simple but good food, concentrated around small dishes. When someone traveled to Vienna, they were sure to include a visit to the café. It was, so to speak, a must-see. However, the café only really came to be famous when the literati, who frequented them, entered the stage representing the intellectuals. The young and cheeky writers were also known to spend very little money when at the café, but they brought (paying) admirers who watched them writing or discussing for hours from neighboring tables. What newspapers does Hugo von Hofmannsthal read? And which one first? You could find out at Café Griensteidl. You did not even have to get up early, because Mister Hofmannsthal didn’t usually show up before 11 a.m. Who is Arthur Schnitzler meeting today? Everyone at Café Central could tell you. And the tabloids were there from the start.

At the end of the nineteenth century the Viennese coffee house became the focal point of upscale Viennese gastronomy and many cafés turned into café-restaurants, large premises with simple but good food, concentrated around small dishes. When someone traveled to Vienna, they were sure to include a visit to the café. It was, so to speak, a must-see. However, the café only really came to be famous when the literati, who frequented them, entered the stage representing the intellectuals. The young and cheeky writers were also known to spend very little money when at the café, but they brought (paying) admirers who watched them writing or discussing for hours from neighboring tables. What newspapers does Hugo von Hofmannsthal read? And which one first? You could find out at Café Griensteidl. You did not even have to get up early, because Mister Hofmannsthal didn’t usually show up before 11 a.m. Who is Arthur Schnitzler meeting today? Everyone at Café Central could tell you. And the tabloids were there from the start.

Karl Kraus, Felix Salten, Egon Friedell or Franz Werfel turned Viennese cafés into their public living rooms. Only those who already had a typewriter – it’s said that Karl Kraus was the only one who did – retired to write at home. The others regularly opened up their notebooks in the café and wrote some of their best works, surrounded by all the noise, hustle and bustle. It wasn’t as much about being inspired by the coffee house, but rather about making their presence known to the public. It heightened the sales of their books. The Viennese coffee house literati were the first pop stars in history and at the same time the first generation of writers, who – for those times – earned a great deal of money with their works, which had previously been regarded as unprofitable, thus escaping their usually petty-bourgeois conditions. They made the café a meeting place for people who sought freedom of speech and writing. The police secret service also sent their agents to the coffee houses, but these inconspicuous informers were so striking that Karl Kraus couldn’t help himself from publicly revealing them from time to time.

Felix Salten wrote parts of his pornographic novel “Josefine Mutzenbacher. The Life Story of a Viennese Whore” in various Viennese cafés. That’s what the journalist-savvy gossipers Karl Kraus and Egon Friedell said, at least. Salten himself, who later sold the rights for “Bambi” to Disney, never confessed to the work, although it unmistakably carries his handwriting. In typical Viennese fashion of the times, the book escaped censorship through pre-orders. Only when a Berlin newspaper became infuriated by the contents, Viennese politicians began prohibiting it. All copies of the Mutzenbacher had already been sold. The skilled Viennese knows what I am talking about.

Its reputation as a literary hub has been maintained by Viennese coffee houses to this day, even if hardly any authors write their books there anymore. Instead, authors love doing interviews at the café. Nowadays, the relatively young Café Engländer is a favorite meeting spot for journalists. They like to speak conspiratorially, just like in the days of Diodato. Knowing full well that they are being watched by everyone around them. The skilled Viennese … Well, you already know what I mean.

Text : MANFRED KLIMEK

Share On Facebook

Share On Facebook Tweet It

Tweet It